THE WOUND AND THE KNIFE

By Alberto Giudici

On the occasion of D. Zorreguieta's solo show "love/romance" at CoBra Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen.

Since her first solo exhibition in Buenos Aires (Galería Van Riel) in 1988, Dolores Zorreguieta has worked with a great variety of techniques and media. But despite this diversity of expression means, a delicate and extremely sensitive connecting thread runs through her oeuvre in the form of a constantly recurrent, tormented and cutting exploration of human relationships. A particular target are those between men and women. For the tensions of sexuality – a meeting point and a divisive element between the sexes at the same time – there is no way out, and we are left with the big vital question. That is, the question of existence and the continuing of life with its troubled conscience. For Zorreguieta, the very complex structure of human relationships, even in their most intimate forms of expression like attachment and love, is founded on power. Within that web of power balances, each being clings to their own self like a huddled wild animal –helplessly abandoned but also fending off. Existence is defense that became an attack. As Zorreguieta herself says, quoting Baudelaire: ‘I am the wound and the knife’. A wolf on the infinite and inaccessible prairies of the human condition.

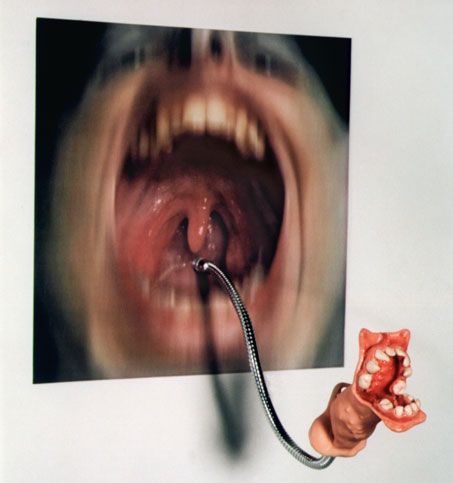

In March 2001 an exhibition Autorretrato (Self-Portrait) was organized in Buenos Aires as part of International Women’s Day. Twenty-six curators chose work from a hundred thirty-one leading Argentinean female artists spanning three generations. Zorreguieta’s entry was extremely revealing. It consisted of a digitally manipulated photographic portrait in which her face had been cropped in such a way that her aggressively wide open mouth dominated the image. A metal thread appeared from the depths of her throat – the photograph was focused on her larynx – on which a small clay monster was attached with jaws just as fierce looking as hers. Similar in fact to the images now on view at the Cobra Museum. This depiction of shrieking rage explains the title of the work Yo quería ser indómita (I want to be untamable), a revelation perhaps of an unrealized fantasy, the symbolic depiction of an unfulfilled wish. Within the context of the exhibition it was an indirect reaction to the role Zorreguieta as a woman is destined to have in relation to her immediate world.

The gender aspect in Zorreguieta’s work is indeed unmistakable, but it also acts chiefly as a means of indicating from which perspective she views the sense of being torn apart that follows her. ‘My work is centered on the primal wounds caused at early age and the ongoing negotiation between us and that pain,’ she explains. The self-reference in her work, arising from her being a woman, is not autobiographical as such, at least not in a literal manner. It is better to state that the artist’s starting point is her own deepest and often painful experiences and based on these she constructs a philosophy of life. She often uses words like wounds or torn open when she is describing her work. The title of her third solo exhibition in Argentina (at the Centro Cultural Recoleta) in 1995 was even titled ‘Heridas: obras sobre papel’ (Wounds: Works on Paper). A year later in July 1996 she made a considerably large work (140 x 200 cm) in which she combined pigment and acrylic paint. On the right-hand side of the canvas a photograph is depicted of Zorreguieta as a small child. With a terrifying look in her eyes she watches as an immense, bloody monster with an enormous head and wide open jaws charges towards her. This oppressive painting entitled Loli and the Monster may be seen as a pendant to the photographic self-portrait in which the monster appears out of herself. We can assume that they are one and the same: they are part of her childlike fears, her tormented self. As Kierkegaard put it in his book A Life of Doubt: ‘Eternity has not acknowledged you, she has not recognized you, or, worse still, she pins you down, and on your self, on your doubting self’! The tragic fate of the Prometheus creator, condemned because he turned against the plans of the gods.

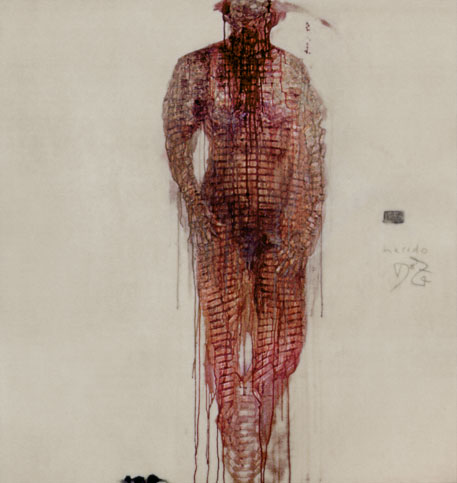

This resistance and encumbrances could also be seen three years ago when Zorreguieta exhibited part of the work she made in the nineteen nineties at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires. A wounded, disfigured female body covered with band-aids, together with old family photographs, formed the key motif of a series of paintings shown. It was work of an overwhelming visual force. In The Wounded Body, an acrylic, 160x 160 cm painting from 1995, Zorreguieta shows us a body swaddled from top to toe in band-aids, but even these do not succeed in stemming the flow of blood. The band-aids placed in rows are like the mesh of a net trying to cover the disfigured body but to no avail. Recently, during the mounting of her exhibition at the Cobra Museum, the artist said she was not afraid of obsessively repeating the same central idea in her work, especially since she always uses new visual forms of expression for this. The bloody ‘fabric’ in The Wounded Body from ten years ago immediately springs to mind when looking at her recent work The Net, which measuring 375 x 400 x 400 cm is the largest in the show. According to the artist, parts of this net hanging from the ceiling resemble gory entrails. Whilst she was setting up the work, someone asked how she was supposed to arrange it – was it a safety net trapeze artists use or was it a net for catching things? ‘That’s exactly what it’s all about’, Zorreguieta explains, ‘It is this ambiguity that precisely interests me. I’d also like to add that we don’t know if the net is soaked with the blood of a victim or that the net itself is a creature that has been taken captive. I personally sense it’s an animal’. Victim or victimizer – the net can act as protection or be a wounded creature.

We see a similar ambiguity in Quilt – a reference to the traditional bed coverings in rural America made from various pieces of fabric sewn together. The squares are attached to each other with black thread and the work, the size of a double blanket, lies on the ground, but has not been entirely smoothed out. According to the artist when people see the work they have the feeling it is flesh: ‘This was also my intention – flesh torn apart’.

This playing around with ambiguous symbiosis is a constant in her work and forms the pulse of her entire oeuvre, one which she sees as a major piece of music in which each work is a variation on the same theme. This fact is not insignificant, as in her work the formal solutions always form the cornerstones of the narrative structure. The boundary between the bearer of meaning and meaning itself is vague. The process is the content of her work.

A good example of this is WE, a 13-minute video capturing fragments from the life of an arbitrary couple which are full of tension, uneasy silences and mutual resentment, and which are intermittently vented in the recalling of past good times or in outbursts of mutual recrimination concerning an inevitable deterioration in the relationship. Weight is added to this everyday scene by the chosen manner of working. The artist has taped off most of the screen so that only a vertical rectangle remains, like a kind of door. The narrative is taking place on the other side of this so that the viewer is forced into the uneasy role of voyeur. As in Hitchcock’s famous film Rear Window the viewer is tied to one perspective. In the film this is the one of the main character who, confined to a wheelchair, strings together various fragment she witnesses into a possible murder plot. The same pattern is repeated in WE: the sealed off screen is an obstruction that prevents access to the scene so that the viewer is denied participation in the illusion of reality. Meanwhile the characters appear and disappear before the camera lens – and thus from those watching – which means only an uninterrupted, incomplete narrative is documented. The whole emanates an atmosphere of silence, emptiness, aversion, melancholy and an intense sense of loss.

This way of creating distance recurs in Fotonovela (Photonovel), albeit with a different aim. Here it is in the form of an installation consisting of a row of 66 very small lockets attached to the wall and thus forming a kind of frieze. They tell a deliberately banal story, with parodying undertones, about a meeting between a man and a woman, their relationship with each other, the female fantasies about a love in which there is also room for carnal lust, which leads to an ending befitting a similar themed B movie. The story begins with a photograph of the grinning, hopeful face of the woman and ends with the also grinning but insincere face of the man. Similar to a nineteenth century melodrama, there is no place for shades of meaning in this photonovel: the end is either ‘happy ever after’ or explicitly tragic, whereby the woman is victimized as divine justice for transgressing the ban on lust. The photographs in the medallions are only 1.6 x 2.1 cm, yet each one has the same disturbing effect as the framework of the earlier described video. The viewer is coerced into a detailed and obscene form of voyeurism that makes you an accessory to the story you are looking at about life and death, and one in which you can ultimately see yourself. In this work the gender viewpoint is no longer covered up but is present both emphatically and provocatively. From the innocent beginning to the bloody conclusion, Fotonovela questions the romantic notions fed by the mass media and the subordinate or perverse role usually set aside for a woman in this.

Zorreguieta describes the creatures in her work as ‘hungry and emotionally deprived.’ As an adage with which to present this hunger and loss, she uses the title of Carson McCullers’ book The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. This is no accidental choice. McCullers, who like the majority of writers from the southern United States sought an answer to the misogynist, racist and reactionary world surrounding them, belongs to the first authors in literature to write about women from a female perspective. Typical of this type of literature is a tragic atmosphere in which the female leading character is the victim of a hostile and oppressive environment. The heart, like a lonely hunter, engages in an unequal struggle, the same kind we find again, on a much more symbolical level, in the challenging and almost offensive tone of Zorreguieta’s work. This paradigm change is noticeable in all forms of visual art where the image of women was, until recently, defined by men. In Notes on Women’s Cinema, a writing considered one of the first exponents of the feminist essay, the English author Claire Johnston writes in 1973: ‘In the male dominated and sexist ideology film world the woman is presented as a representation. The emphasis is on the woman as a spectacle; the woman as a woman is absent however’. In Fotonovela Zorreguieta explains this situation most clearly. The bloody ending, she stresses, cannot be separated from all the other blood and wounds in her work. They mark a turning point. Her creatures change from the male image into actresses and their wounds embody their inward search for their female identity.

‘In my video work, the characters are either longing for something that does not come or mourning for something long gone. In any case, they seem to be suspended in the melancholy of absence, going in circles as in a limbo of unconcluded sorrow. This video work stands in shocking contrast with my mixed media pieces. While the former emanates an evocative poetry, the latter, with their organic nature, embody a visceral and massive presence. The polarization born of this contrast strongly marks my work of recent years. At its roots, we feel the struggle to negotiate the ambivalent instincts of the human experience. An always unresolvable identity split’, according to Dolores Zorreguieta.

The Monstruos (Monsters) series, on which she has been working for several years, dramatically expresses this ambivalence which the artist herself experiences as an unresolved human condition. The monsters are made from ceramic and acrylic and resemble entrails, or reptiles with gruesome teeth. Apart from Self-Inflicted Wound in which the monster is devouring itself, the series is almost always about couples. Some couples are involved in a wild fight, while others lack any possibility of contact. In the case of her recent Joined by the Head, each couple is one. it is about Siamese twins doomed to live together in the same body, but in fact unable to communicate with each other. Their mouths cannot touch each other, neither for a kiss, nor to devour each other. The impotent rage is in the form of a terrifying scream. The loneliness is absolute, even in, or perhaps due to, this enforced togetherness. Another pair, Yin-Yang, are mutually devouring each other in a grisly manner. Based on Eastern philosophy Yin and Yang are two opposites that complement each other and become one within the perfect harmony of a circle. Perhaps Zorreguieta’s offbeat vision is a clue that can give us access to the key to her work, in which again it seems to be about the ambiguous and insoluble struggle with pain which runs throughout her entire work.

Jorge Glusberg, the former director of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, places Zorreguieta’s work alongside Neo Conceptualism of the nineteen nineties, although in her case we should perhaps describe it as Neo Conceptualism with strong expressionist overtones. However, the self referential in her work, the continual withdrawal and quest within herself, and the almost certainty that our life is a solitary duel between us and our haunting, unhealed wounds, which like a bloody thread runs through work after work, make it difficult to categorize her art within a clear-cut contemporary art movement. Perhaps this is also not that important, seeing that her creative imagination is fed by a continual dialogue between that one great vital question and a vulnerable spirit, which is open to various expressive subject matter her everyday surroundings provide.

Buenos Aires, 2005

Alberto Giudici (Buenos Aires, 1941) is a filmmaker, art critic and curator. Since the nineteen seventies he has worked for numerous Argentinean publications. He is currently art critic for the cultural supplement of the Clarín newspaper in Buenos Aires. In 2002 he curated the exhibition Arte y Política en los ’60 (Art and Politics in the1960s), which was declared Best Group Exhibition of the Year by the Argentinean Association of Art Critics. Its accompanying catalogue was awarded a prize for best research. His most recent project as curator is the exhibition Hay que comer (One has to Eat) by the painter Carlos Alonso for the IVAM, Valencia, Spain (March-April, 2005).